Author: Alistair Keiller

Onboarding

Relevant coding background to understand DAC

Cargo: Guide (sections 1-2, optionally 3)

Iced.rs: Short Guide

Tokio.rs: Tutorial

Relevant hardware background to understand DAC

Raspberry Pi 5: Fun Video

Teensy 4.1: Fun Video

CAN protocol: Video

Codebase overview

Here is our codebase: https://github.com/Anteater-Electric-Racing/embedded

fsae-dashboard

This dashboard displays current critical information to the driver

This dashboard displays current critical information to the driver

fsae-raspi

This runs an mqtt broker, influxdb server, grafan server, and polls all correctly formatted isotp can data aoff of /dev/can0 to send to both mqtt and influxdb.

Author: Mikayla Lee

CAN

AER Telemetry over CAN ISO-TP

CAN ISO-TP Telemetry Receiver & Test Pipeline

Overview

This system receives telemetry data from the motor controller over CAN using ISO-TP, decodes the packet into strongly typed data, and forwards it for downstream processing. It also includes test utilities for transmitting and validating telemetry over a virtual CAN interface (vCAN) in CI.

Workflow

CAN ISO-TP Data Reception

- Listens on the physical CAN interface (

can0) using ISO-TP sockets - Receives multi-frame telemetry packets from the motor controller

- Validates packet length (expected: 58 bytes)

- Decodes raw bytes into typed telemetry fields

Telemetry Parsing

- Converts byte slices into numeric values (

f32,i32) using little-endian decoding - Maps state and mode bytes into enums representing motor and MCU state machines

- Parses fault flags into boolean values

- Assembles all decoded values into a

TelemetryDatastructure

Telemetry Forwarding

- Wraps decoded values in a

TelemetryDatastruct - Publishes telemetry via

send_message() - Uses the “telemetry” topic for downstream consumers

ISO-TP Test Transmission (vCAN)

- Serializes

TelemetryDatausingbincode - Sends telemetry as a single ISO-TP packet over

vcan0 - Used exclusively for testing and CI validation

Key Features

- Strongly Typed Telemetry – Enums and structs ensure safe decoding of MCU and motor states

- Resilient Socket Handling – Automatically retries socket creation on failure

- Clear Packet Contract – Enforces a strict 58-byte telemetry frame layout

- CI-Friendly Testing – vCAN-based tests run in GitHub Actions

- Extensible Design – New telemetry fields and enums can be added with minimal refactoring

Telemetry Data Summary

Struct: TelemetryData

Purpose: Represents a fully decoded MCU telemetry packet received over CAN ISO-TP

Contents:

- Driver input: accelerator pedal travel (

apps_travel) - Motor metrics: speed, torque, max torque, direction, state

- MCU status: main state, work mode, voltage, current

- Thermal data: motor and MCU temperatures

- Fault flags: over-voltage, over-current, stall, phase current, overspeed

- Warning level: MCU warning severity

- Debug channels:

debug_0–debug_3

Enum Definitions

MotorState

- Off

- Precharging

- Idle

- Driving

- Fault

MotorRotateDirection

- Standby

- Forward

- Backward

- Error

MCUMainState

- Standby

- Precharge

- PowerReady

- Run

- PowerOff

MCUWorkMode

- Standby

- Torque

- Speed

MCUWarningLevel

- None

- Low

- Medium

- High

Each enum includes a from_byte() constructor for safe decoding from raw CAN payloads.

CAN Reader Summary

Function: read_can

Purpose: Continuously reads and decodes telemetry packets from can0

Workflow:

- Attempts to open an ISO-TP socket (retries on failure)

- Reads incoming packets asynchronously

- Validates packet length

- Parses raw bytes into

TelemetryData - Forwards decoded telemetry via

send_message()

Error Handling:

- Logs socket creation failures

- Logs malformed packet lengths

- Continues operation without crashing

Test: ISO-TP Telemetry Transmission

Test: test_send_telemetry_over_isotp

Purpose: Verifies ISO-TP telemetry transmission over a virtual CAN interface

Steps

1. Prepare Test Data

- Creates a

TelemetryDatainstance with representative values

2. Send Telemetry

- Serializes the struct using

bincode - Transmits the packet over ISO-TP on

vcan0

3. Validate Environment

- Uses vCAN setup provided by the GitHub Actions workflow (

test.yml) - Confirms ISO-TP send path functions correctly

Key Points

- Uses

tokio_socketcan_isotpfor asynchronous CAN ISO-TP communication - Clean separation between production (

can0) and test (vcan0) interfaces - Designed for reliability in embedded deployment and CI environments

- Documentation aligns directly with packet structure and test behavior

Author: Alistair Keiller

InfluxDB

CAN-to-InfluxDB Telemetry (Line Protocol)

Transforms strongly-typed telemetry readings into InfluxDB Line Protocol after MQTT verification. The key helper is to_line_protocol, which turns any Reading into a write-ready line.

Function: to_line_protocol<T: Reading>(message: &T) -> String

- Measurement: Uses

T::topic()as the measurement name. - Fields: Serializes number, string, and boolean fields; unsupported types are skipped.

- Timestamp: Appends current UTC time in nanoseconds.

Field Formatting

- Integers (

i64,u64): Suffixed withi, e.g.,rpm=1200i. - Floats: Written as-is, e.g.,

voltage=12.34. - Strings: Quoted, e.g.,

state="OK". - Booleans: Lowercase

true/false.

Example Output

- Input:

TelemetryData { rpm: 1200, voltage: 12.34, state: "OK", fault: false } - Topic:

telemetry - Output:

telemetry rpm=1200i,voltage=12.34,state="OK",fault=false 1734043200000000000

Workflow Inside to_line_protocol

- Start with

T::topic()as the measurement. - Serialize

messageto JSON (serde_json::to_value). - Iterate object fields, formatting supported values and comma-separating them.

- Append the UTC nanosecond timestamp from

chrono::Utc::now().timestamp_nanos_opt(). - Return the completed line protocol string.

End-to-End Flow

- Collect CAN telemetry (speed, torque, voltage, current, temps, fault states) into a

TelemetryDatathat implementsReading. - Publish the struct as JSON to the

telemetryMQTT topic with QoSAtLeastOnce. - MQTT listener verifies the payload matches the expected

TelemetryData. - On verification success, convert to line protocol via

to_line_protocoland write to InfluxDB.

Writing to InfluxDB

- Endpoint: HTTP

POST /api/v2/write?org=<org>&bucket=<bucket>&precision=nsor the official Influx client. - Body: The string returned by

to_line_protocol. - Auth:

Authorization: Token <token>header. - Precision:

nsto match the timestamp source. - Reliability: Add retries/backoff for transient failures and log write errors.

Minimal sketch:

let lp = to_line_protocol(&telemetry);- POST

lpto the write endpoint withprecision=ns.

Testing Guidance

- Unit tests: verify integer

isuffixing, string quoting, boolean casing, and timestamp inclusion. - Integration: pair with the MQTT listener test to cover publish → verify → convert → write.

Troubleshooting

- Missing fields: Ensure fields are serde-serializable scalars (no nested objects/arrays).

- Wrong measurement: Confirm

T::topic()returns the intended measurement. - Write failures: Check token, bucket, org, precision, and server availability.

- Timestamp

None: Verify system clock andtimestamp_nanos_opt()support on the target platform.

MQTT

Author: Lawrence Chan

CAN-to-InfluxDB Telemetry Pipeline via MQTT

Overview

This system reads data from a CAN bus, sends it through MQTT, verifies the packet, and stores it in InfluxDB.

Workflow

-

CAN Bus Data Collection

- Reads telemetry values such as motor speed, torque, voltage, current, temperatures, and fault states.

- Packages data into a

TelemetryDatastructure.

-

MQTT Transmission

- Publishes

TelemetryDatato the"telemetry"topic on the MQTT broker. - Ensures reliable delivery using QoS

AtLeastOnce.

- Publishes

-

MQTT Listener Verification

- Subscribes to the

"telemetry"topic. - Converts incoming MQTT payload bytes to UTF-8 strings.

- Deserializes JSON into

TelemetryData. - Compares received data against expected telemetry for verification.

- Returns

trueif verification succeeds.

- Subscribes to the

-

InfluxDB Storage

- On successful verification, telemetry is stored in InfluxDB.

- Each parameter (e.g., motor speed, voltage, fault flags) is stored as a separate measurement or field for time-series tracking.

Key Features

- Real-Time Monitoring: Data flows from CAN bus → MQTT → verification → InfluxDB.

- Error Handling: Logs failed subscriptions, parsing errors, or deserialization issues.

- Test Coverage: Includes asynchronous tests to ensure listener correctly receives and verifies messages.

- Extensible: Can add new telemetry fields or modify verification rules without disrupting the pipeline.

MQTT Listener Verification Summary

Function: verify_mqtt_listener

- Purpose: Verifies that an MQTT listener receives a specific telemetry message.

- Parameters:

telemetry_struct: TelemetryData– the expected telemetry data to verify against. - Returns:

bool–trueif the message is received and matches, otherwisefalse.

Workflow

-

Setup MQTT Client

- Creates an

AsyncClientwith a 5-second keep-alive. - Connects to

MQTT_HOSTandMQTT_PORT.

- Creates an

-

Subscribe to Topic

- Subscribes to

"telemetry"topic with QoSAtLeastOnce. - Logs an error and returns

falseif subscription fails.

- Subscribes to

-

Listen for Messages

- Polls the event loop for incoming packets.

- Timeout: 1 second.

- On

Publishpackets:- Converts payload bytes to a UTF-8 string.

- Deserializes JSON into

TelemetryData. - Returns

trueif it matchestelemetry_struct.

-

Error Handling

- Logs conversion or deserialization errors.

- Returns

falseif no matching message is received or timeout occurs.

Test: test_verify_mqtt_listener

- Purpose: Ensures

verify_mqtt_listenercorrectly detects the telemetry message.

Steps

-

Prepare Test Data

- Creates

TelemetryDatawith default values and states.

- Creates

-

Run Listener

- Initializes a Tokio runtime.

- Spawns

verify_mqtt_listenerasynchronously.

-

Send Test Message

- Sleeps for 500 ms to allow the listener to start.

- Sends the test telemetry message via

send_message.

-

Validate

- Waits for listener result.

- Asserts that the listener received the expected message.

- Logs failure if the message was not received.

Key Points

- Uses asynchronous MQTT client (

rumqttc::AsyncClient). - Handles message parsing, deserialization, and matching safely.

- Includes robust error logging for debugging.

- Test ensures integration works in a runtime environment.

Onboarding

Author: Karan Thakkar

Relevant coding background to understand firmware

C++ reference and language: cppreference.com PlatformIO: platformio.org — helpful for faster prototyping and device management.

FreeRTOS official site and API reference: freertos.org

Debugging & diagnostics

- TBD (openCD?)

Relevant hardware background to understand firmware

Teensy 4.1: PJRC Teensy 4.1 - MCU board used in our stack

CAN protocol: Video

Custom PCBs

CCM

Controls all the sensor inputs + outputs and perform motor control calculations.

PCC

Automates the battery precharge sequence to mimize instaneous capacitor charging.

Codebase overview

Here is our codebase: https://github.com/Anteater-Electric-Racing/embedded

fsae-vehicle-fw

Contains all vehicle firmware for CCM (sensor interfacing + motor controls)

fsae-pcc

Contains all firmware for PCC sequence.

Author: Karan Thakkar

System Architecture

---

config:

theme: 'base'

themeVariables:

primaryColor: '#ffffffff'

primaryTextColor: '#000000ff'

primaryBorderColor: '#17007cff'

lineColor: '#000000ff'

secondaryColor: '#f3f3f3ff'

tertiaryColor: '#f3f3f3ff'

---

flowchart BT

%% This is a comment for the entire diagram

subgraph CAN[" "]

BMS(Orion BMS 2)

BC(Battery Charger)

PCC(PCC - Teensy 4.0)

INV(OMNI Intervter)

RPI(Raspberry Pi)

MOTOR(Motor) === INV

end

CCM(CCM - Teensy 4.1)

%%CAN LOOP1

BMS <--> |CAN1| BC <--> |CAN1| PCC <---> |CAN1| CCM

%%CANLOOP2

INV<-----> |CAN2|CCM<---> |CAN1 + CAN2|RPI

subgraph Analog[Analog]

direction LR

B(Brake Sensors)

A(Pedal Position Sensors)

LPOT(Suspension Travel Sensors)

TR(Thermistors)

end

subgraph PWM[PWM]

direction LR

W(WheelSpeed Sensors)

FP(Fans & Pumps)

SP(Speaker & Amp)

end

subgraph MISC[Digital]

direction LR

RTM(Ready To Move Button)

BL(Brake Light)

end

Analog --> CCM

PWM --> CCM

MISC -->CCM

---

config:

theme: 'base'

themeVariables:

primaryColor: '#ffffffff'

primaryTextColor: '#000000ff'

primaryBorderColor: '#17007cff'

lineColor: '#000000ff'

secondaryColor: '#f3f3f3ff'

tertiaryColor: '#f3f3f3ff'

---

flowchart LR

PCC(Precharge Status) --> CCM

A(Analog Inputs) --> CCM

D(Digital Inputs) --> CCM

CCM(Teensy MCU) --> IC(Inverter Commands) --> Motor(Motor Control)

CCM --> Raspi(Raspi) --> Dashboard(Dashboard: Driver + Pit)

CCM --> PWM(PWM Output) --> CC(Cooling Control)

style CCM fill:#00FF00,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

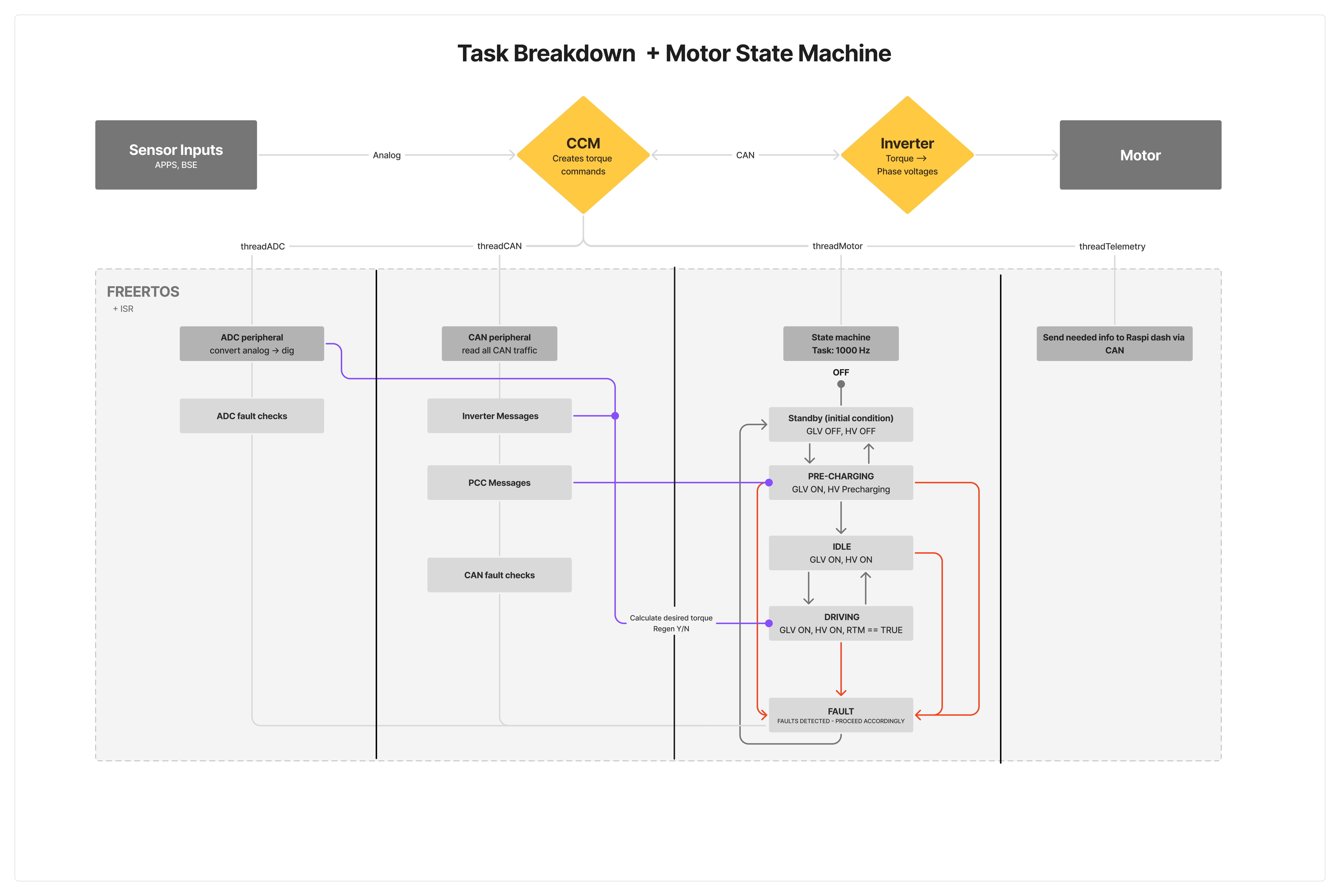

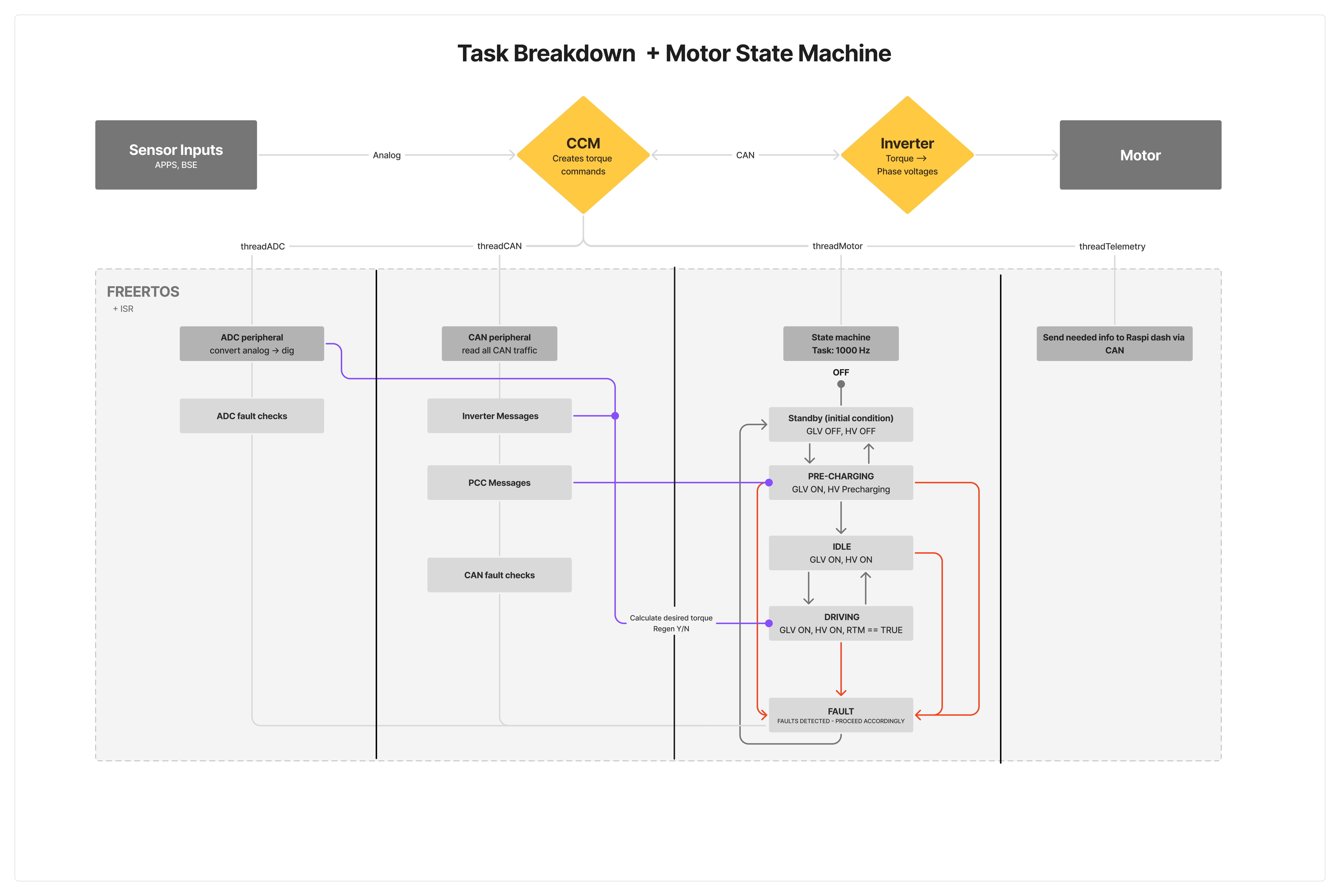

Tasks and Threads

Author: Karan Thakkar

CCM: Central Computer Module

CCM is the main central vehicle board. Its main purpose is to acquire data from sensors across the car, use it in vehicle control commands and send over CAN to our Raspberry Pi.

CCM is powered by (1) Teensy 4.1 MCU which runs an ARM-Cortex-M7. We write our firmware in C++ and flash it to our board. The board communicates with various devices over analog, digital, CAN and i2C.

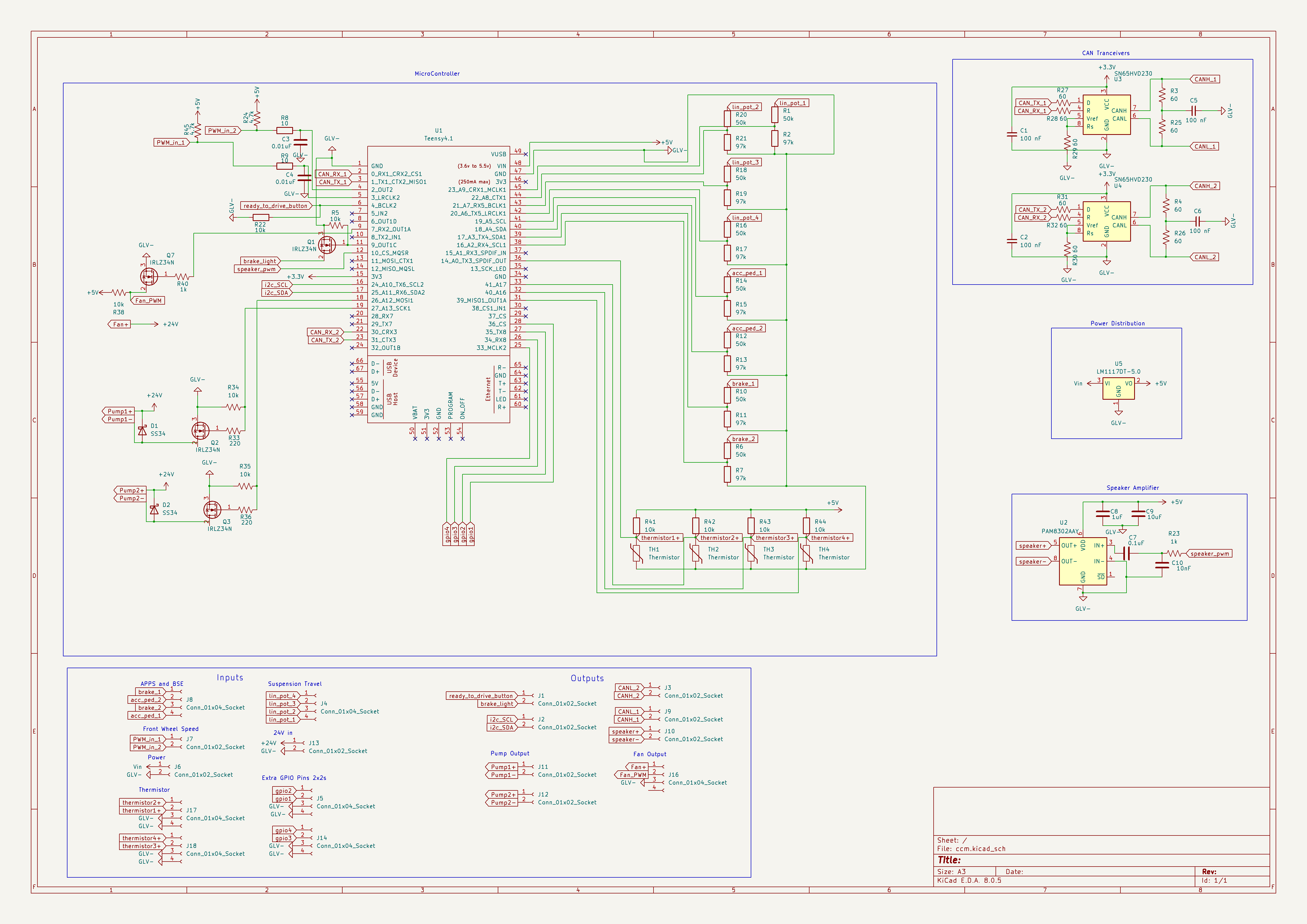

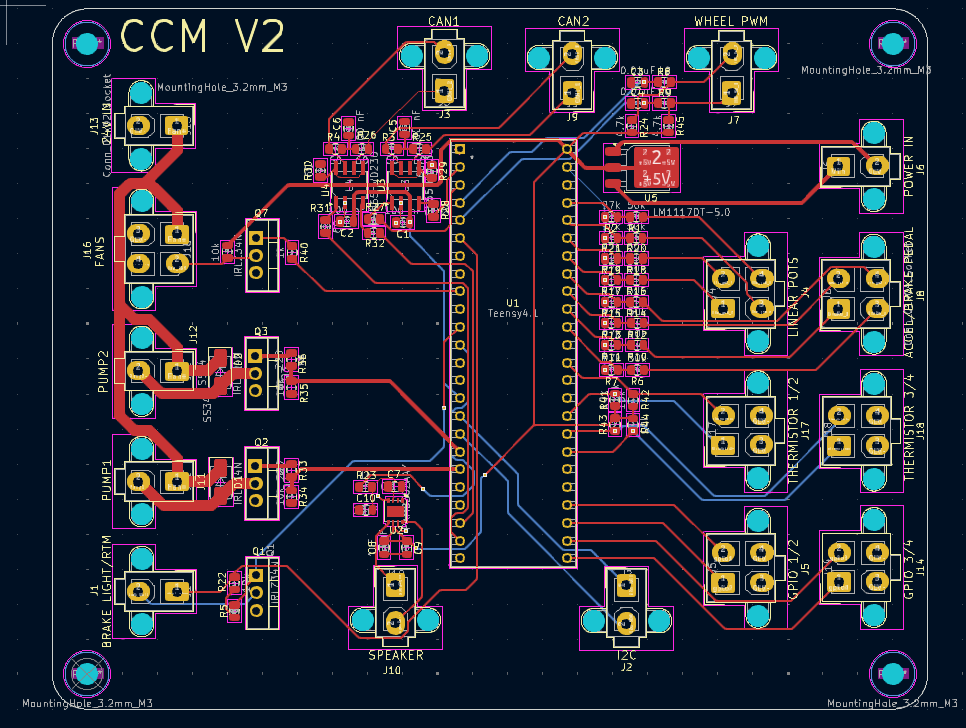

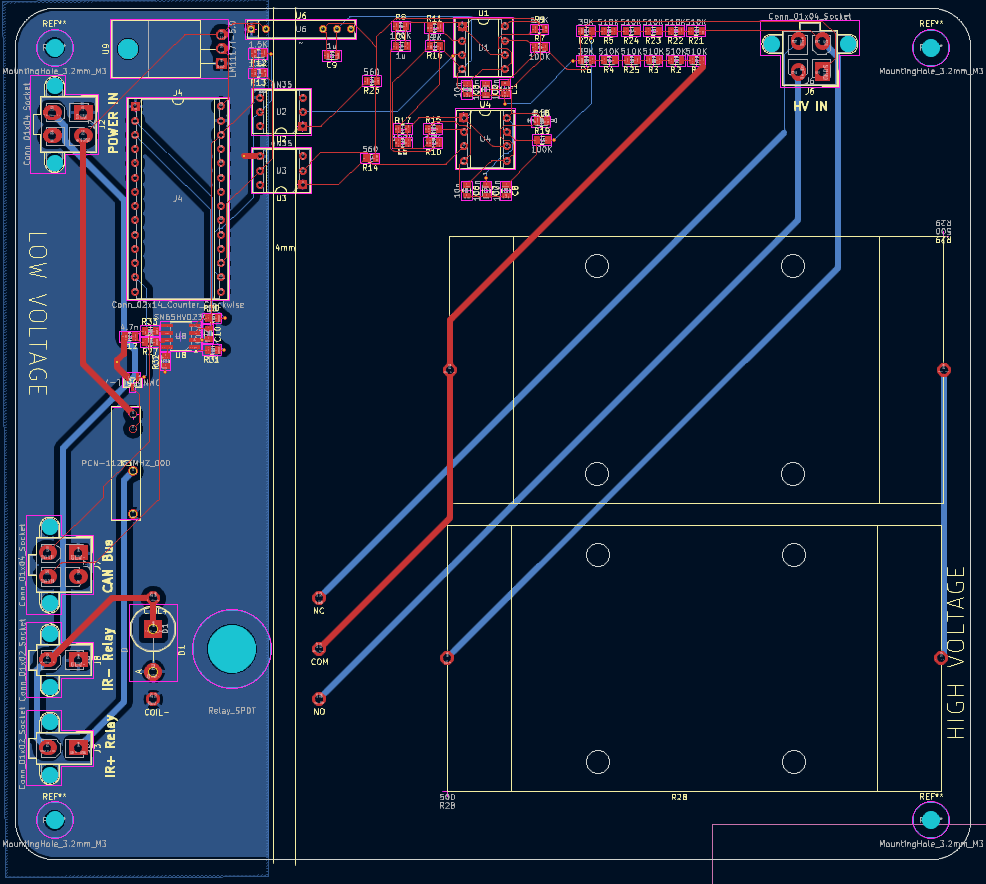

The full kicad files can be found here.

Current Version: 2.0

Schematic

- The top left shows the MCU pinout

- The top right shows the CAN Tranceiver setup

- The bottom shows the I/O

PCB Layout

- The Right side holds all the analog inputs + 12v Power in

- The left side holds CAN1/CAN2 + PWM outputs from CCM as well as misc inputs.

Improvements

This board has planned improvments for a version (3.0) Some new features include

- More sensors inputs (Tire Temp, Brake Temp, Steering Wheel Angle)

- Input for Inverter Keyswitch (KL15)

Author: Karan Thakkar

Peripherals

Digital I/O

RTM (Ready To Move) Button Input

The RTM input is handled as a standard digital GPIO read. It functions as a momentary push-button with software debouncing to avoid false triggering from mechanical bounce. Each press toggles the latched internal state between 0 and 1, allowing the system to reliably detect transitions. This signal is used in the vehicle state machine to move the car from the IDLE state into the RUNNING or DRIVE state once all safety conditions are met.

Brake Light Output

The brake light is driven as a digital output that activates based on braking conditions. Depending on system rules and logic, this signal can be turned on when:

- Brake pressure exceeds a threshold

- Regenerative braking torque is applied above a defined amount

- Other system-defined braking conditions are met The output is typically a high-side digital drive that activates the physical brake lamp in accordance with FSAE regulations.

WheelSpeed Sensors (Front) Input

Front wheel speed sensors are hall-effect pickups producing a square-wave digital signal proportional to wheel rotation. The frequency of the pulses corresponds to wheel speed, allowing RPM to be computed from:

- The frequency of the input pulses

- The known number of sensor teeth or magnets

- Wheel circumference and drivetrain ratios

From this, speed and wheel rotational dynamics can be calculated for traction control, odometry, telemetry, and dynamic vehicle control.

Fans & Pumps Output

Two MOSFET-controlled outputs are available for driving the cooling fan and coolant pump. These are controlled through software feedback loops that monitor thermistor temperature readings. When temperature increases beyond a target setpoint, fan or pump duty cycle increases proportionally. When temperatures fall below defined limits, duty cycle is reduced. This provides automatic thermal regulation for the accumulator or power electronics cooling loop.

Speaker Output

Audio signaling is performed using a PWM output connected to an amplifier which drives the speaker. This is used to produce audible alerts per competition requirements, such as:

- Ready-to-drive tone

- Fault indication tones

- System status alerts

The speaker system ensures the car meets FSAE safety requirements for audible signaling before the drivetrain engages.

Analog I/O

Brake System Encoder

A linear analog pressure transducer is used to measure hydraulic brake line pressure. The voltage is read via an ADC and mapped into engineering units using a calibration curve. Brake pressure is used to:

- Smoothly blend mechanical and regenerative braking

- Block acceleration torque while braking

- Activate brake lights

- Support telemetry and control algorithms

This sensor is part of multiple safety-critical paths and must be sampled and checked reliably.

Acceleration Pedal Position

The accelerator pedal position sensor outputs a variable voltage proportional to throttle demand. The reading is converted into a normalized torque request and fed into the torque controller. For safety, dual redundant channels are commonly monitored, and mismatches are checked to detect faults such as wiring damage or sensor failure. If readings disagree beyond limits, torque is disabled and a fault is raised.

Suspension Travel

Suspension position is measured by analog linear potentiometers These readings allow:

- Logging for vehicle dynamics analysis

- Dynamic control adjustments such as damping or traction control

Thermistors

Thermistors measure temperature in critical subsystems such as:

- Motor controllers

- Batteries and accumulator modules

- Cooling loops

- Power electronics

These readings are used in closed-loop thermal regulation. Raw voltage readings are converted using standard thermistor curve equations or lookup tables. If temperatures exceed defined safety thresholds, torque may be reduced, cooling activated, or the vehicle shut down depending on severity.

CAN

BMS

The Battery Management System communicates via CAN, sending essential data such as:

- Cell voltages

- Module temperatures

- Current consumption

- State-of-Charge and State-of-Health

- Fault flags and system warnings

The control system must consume these messages to maintain safe vehicle operation. If BMS signals a critical fault, the drivetrain must disable torque output immediately.

Battery Charger

During charging mode, the onboard charger exchanges CAN messages with the BMS and vehicle controller. Messages include:

- Charging current and voltage targets

- Charge state progress

- Fault and error reporting

The charger generally follows BMS instructions to ensure safe constant-current and constant-voltage charging curves.

PCC

The PCC (Pre Charge Circuit) communicates over CAN to exchange infor with the CCM. Data typically includes:

- Precharge state

- Precharge Progress

- TS/Accum Voltage read over frequency to voltage circuits

- Precharge time

The PCC and CCM coordinate to ensure safe charing of the inverter and HV side. Read more about this in the PCC section.

CCM

The CCM (Central Computer Module) acts as the main MCU for car.

- Broadcast system heartbeat messages

- Reads all sensor readings

- Receive driver input and button states

- Relay fault conditions

- Coordinate operation between subsystems

- Sends torque commands to the Inverter based on all readings

- Relays info to telemetry side.

Author: Karan Thakkar

Vehicle Control

Motor/Inverter

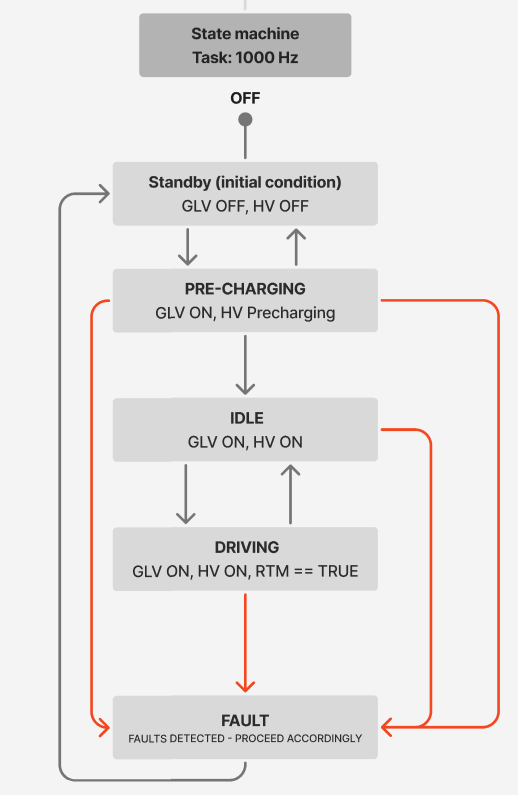

The motor inverter in this system is responsible for controlling how power flows from the high-voltage battery to the traction motor, and its behavior is managed through a well-defined state machine aligned with Formula SAE Electric vehicle requirements.

The inverter is commanded through CAN messages that include torque requests, motor mode, relay control, and system readiness.

Depending on the operating state—such as OFF, STANDBY, PRECHARGING, IDLE, DRIVING, or FAULT—the inverter receives different command values that ensure the vehicle only delivers torque when it is electrically safe to do so. During driving, the requested torque is converted into a percentage value that the inverter understands, while additional parameters like regen mode, gear mode, and allowable currents from the BMS are also communicated. This helps maintain smooth torque delivery and ensures that high-voltage operation meets safety rules set by FSAE.

The transitions between inverter states are based on system conditions such as the Ready-To-Move button, precharge status, BMS confirmations, and overall system health.

For example, the inverter does not enter the DRIVING state until the precharge process has completed, battery relays are confirmed closed, and the driver actively requests propulsion. If communication issues or electrical faults occur, the inverter is immediately commanded into a FAULT state to disable torque and open relays where needed.

By structuring inverter behavior around explicit state transitions and safety checks, the system guarantees predictable and rules-compliant operation while providing clear separation between low-voltage logic and high-voltage power control, which is a core requirement for competition-legal and reliable Formula SAE EV design.

State Machine

Fault Handling

This fault map system uses a single 32-bit variable to keep track of all vehicle faults. Each fault type has its own bit in the bitmap, and when a fault is detected, its bit is turned on. When the fault clears, the bit is turned off. This makes fault storage very compact and fast to check, which is helpful on embedded systems where memory and CPU time matter. The system can quickly tell if any fault is active or look at specific bits to see which ones are triggered.

The handler function then looks at the bitmap and sets the motor into a fault state if any fault is active. Right now, every fault is treated the same, but the structure is flexible enough to customize actions later, such as limiting torque for minor issues or shutting down the drivetrain for serious ones. This design keeps the code organized, easy to maintain, and simple to expand as the system grows.

Purpose

Design a function that optimizes 0–60 mph acceleration by adjusting torque output based on slip ratio.

- Optimal slip ratio ≈ 7% (commonly 5–10% depending on car).

- If slip ratio exceeds optimal → decrease torque

- If slip ratio falls below optimal → increase torque

Algorithm Overview

Initial Function

- Validate and reset PID gains and internal PID state.

- Obtain constants (max torque, optimal slip target).

- Initialize launch control button to false (inactive until pressed).

Update Function

-

Check button state

- If not pressed → output driver torque normally.

-

Wheel speeds

- Controlled speed: rear wheel with higher speed.

- Free rolling speed: front wheel with lower speed.

-

Slip Ratio

- slip = (controlledSpeed - freeRollingSpeed) / freeRollingSpeed

-

Torque Logic

- If slip < 0.05 → increase torque.

- If slip > 0.10 → decrease torque.

- PID Correction

- Run at 100 Hz (

dt = 0.01). - Use

PID::PID_Calculate()for correction. - Add correction to driver torque.

- Clamp Torque

- If corrected torque > max → clamp to maxTorque.

- If < 0 → clamp to 0 Nm.

Implementation Details

void launchControl_Init()

Initializes PID controller values for slip ratio correction.

void threadLaunchControl(void *pvParameters)

LAUNCH_STATE_ON

- Obtain slower front wheel speed.

- Convert rad/s → m/s using wheel radius.

- Motor/rear speed used as controlled speed.

- Compute slip.

- PID applies torque correction.

- Clamp torque within bounds.

- If brakes are pressed → exit to LAUNCH_STATE_OFF.

LAUNCH_STATE_OFF

- Wait for:

- Front brake fully pressed

- Motor speed = 0

- Then activate launch control (FSAE requires button activation — must update logic).

FAULT State

- Triggered by irregular wheel speeds or invalid conditions.

TESTING PLAN

Method Signature:

threadLaunchControl(void *pvParameters)

Constants:

slipTarget = 0.7f

minTorque = 0.0f

maxTorque = 260.0f

wheelRadius = 0.35f

TestCase 1 (base case)

Brake = 60 psi

Motor speed = 0 rad/s

Motor state = MOTOR_STATE_DRIVING

threadLaunchControl()

launchControlState -> LAUNCH_STATE_ON

TestCase 2

wheelSpeedFL = 80 rad/s, wheelSPEEDFR = 82 rad/s, motorSpeed = 80 rad/s

realTorque = 150 Nm

LaunchState = on

Slip ratio = 0.0–0.02 -> small PID correction

torqueDemand = 150 Nm (unchanged to barely changed)

LaunchState = ON

TestCase 3

wheelSpeedFL = 40 rad/s, wheelSpeedFR = 42 rad/s, motorSpeed = 100 rad/s

realTorque = 200 Nm

Slip ratio = (100–41)/41 = 1.43 -> very high slip

PID correction negative -> torque reduced near 0 Nm

torqueDemand = near minTorque = around 0 Nm

TestCase 4

wheelSpeedFL = 100, wheelSpeedFR = 99, motorSpeed = 100

realTorque = 250 Nm, slip slightly below 0.07

PID positive correction increases torque above 260 -> clamped at 260 Nm

torqueDemand = 260 Nm

TestCase 5

LaunchState = ON, BSE_GetBSEReading() -> 80 PSI

APPS_GetAPPSReading() < 1.0

Expected behavior:

PID reset

torqueDemand = rawTorqueInput

launchControlState = LAUNCH_STATE_OFF

Author: Karan Thakkar

Tasks & Scheduling

The firmware is structured using FreeRTOS to split the vehicle control system into separate tasks, each handling its own area. ADC readings, motor control, telemetry, and high-level control all run in their own threads, so critical operations don’t get blocked by slower tasks. For example, threadADC continuously samples analog sensors, while threadMotor handles the motor state machine, updates torque, and communicates with the VCU and BMS over CAN. This keeps motor commands and sensor updates running on a predictable schedule, which is important for safe and reliable operation in the car.

The threadMain task is used for testing and user interaction. It reads input from the serial monitor to adjust torque, change vehicle states, and toggle regen, while also printing telemetry like motor speed, current, and temperatures. threadTelemetry collects and sends key vehicle data over CAN on a regular cycle. Separating everything into different threads makes the system easier to debug, maintain, and expand. FreeRTOS handles scheduling, so high-priority tasks like motor control always run reliably, while less critical tasks like user input don’t interfere.

Watchdog Timer

In Progess

Author: Karan Thakkar

Telemetry

Current Version: HIMaC testing:

telemetryData = {

.APPS_Travel = APPS_GetAPPSReading(),

.motorSpeed = MCU_GetMCU1Data()->motorSpeed,

.motorTorque = MCU_GetMCU1Data()->motorTorque,

.maxMotorTorque = MCU_GetMCU1Data()->maxMotorTorque,

.motorState = Motor_GetState(),

.mcuMainState = MCU_GetMCU1Data()->mcuMainState,

.mcuWorkMode = MCU_GetMCU1Data()->mcuWorkMode,

.mcuVoltage = MCU_GetMCU3Data()->mcuVoltage,

.mcuCurrent = MCU_GetMCU3Data()->mcuCurrent,

.motorTemp = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->motorTemp,

.mcuTemp = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->mcuTemp,

.dcMainWireOverVoltFault =

MCU_GetMCU2Data()->dcMainWireOverVoltFault,

.dcMainWireOverCurrFault =

MCU_GetMCU2Data()->dcMainWireOverCurrFault,

.motorOverSpdFault = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->motorOverSpdFault,

.motorPhaseCurrFault = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->motorPhaseCurrFault,

.motorStallFault = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->motorStallFault,

.mcuWarningLevel = MCU_GetMCU2Data()->mcuWarningLevel,

};

This telemetry section acts as a real-time summary of everything important happening in the drivetrain during HIMaC testing. It records the driver’s accelerator pedal position so we know how much torque is being requested at any given moment. Keeping this information in one place makes it easy to log, monitor, and analyze how the system responds under different conditions.

It also gathers detailed status information from the motor controller, including actual motor speed, delivered torque, voltage, current, and temperatures. These values help confirm that the system is performing as expected and staying within safe operating limits. Along with this, the telemetry captures the current operating modes and internal controller states, giving a clear picture of what the motor system is actively doing.

In addition, the telemetry includes a set of fault and warning indicators that report when something abnormal has occurred, such as overcurrent, overspeed, overheating, or voltage problems. These alerts allow the system to react quickly by limiting torque or switching into a safer mode. Overall, this telemetry structure provides a clean and organized snapshot of the drivetrain’s condition, making testing, troubleshooting, and performance analysis much easier.

All this data is sent over CAN to our Raspberry PI in 1 packet.

PowerLimit_Update()

Purpose

This function ensures the car does not request motor torque which exceeds two important torque threshold requirements. The two cases in which this function would intervene are when max requested power exceeds 80kW (EV.3.3.1) and when the accumulator SOC is < 20%, in which rules specify that we must linearly reduce allowed power down to 0 at 5%.

Structure

Given above is a block diagram of the PowerLimit_update() function. In our codebase, PowerLimit_update() is called inside motor.cpp, during Motor_UpdateMotor()’s MOTOR_STATE_DRIVING state. The variable torqueDemand is given as an argument to Motor_UpdateMotor(), and this is then passed into our function, and finally returned and assigned to motorData.desiredTorque. A function somewhere else in the codebase will then read this value and send it to the motors, creating the actual torque requested.

In addition to torqueDemand, PowerLimit_Update() requires accumulator voltage and current as well as accumulator SOC. Voltage and current are multiplied to find power.

Implementation

There are a few constants used in this method, all of which are defined inside /utils/utils.h. What these all represent and what they are used for are as follows:

SOC_START, SOC_END

Represents the percentage (as a decimal) at which SOC-based torque limiting (derating) begins and ends. As of 10/2025 they are set to .2 and .05, respectively. Derating will begin at SOC_START, and will linearly reduce until reaching SOC_END, when torqueDemand will be 0.

MOTOR_MAX_TORQUE

Represents the maximum torque that the car is designed to output. Measured in N*m. This is used to linearly scale the torqueLimit proportionally based on SOC.

POWER_THRESHOLD_kWh

Represents maximum power allowed in FSAE rulebook. When calculated power is over this amount, driverTorqueCmd gets scaled down by this threshold divided by the calculated power. The assumption behind this is that power and torque are proportional, meaning that when calculated power is 10% above the threshold, driverTorqueCmd gets scaled down accordingly by 10%.

SOC derating amount is calculated and then stored inside the local variable torqueLimit, which is assigned to driverTorqueCmd at the end. Power limiting doesn’t use torqueLimit, it just directly sets driverTorqueCmd.

Testing

Method signature:

PowerLimit_Update(float soc, float voltage, float current, float driverTorqueCmd)

Constants:

MOTOR_MAX_TORQUE = 260.0F

POWER_THRESHOLD_kWh = 90

SOC_START = 0.2

SOC_END = 0.05

Test case 1 (base case):

PowerLimit_Update(.25, 40, 2, 200);

Returns 200

Test case 2 (MOTOR_MAX_TORQUE condition checking):

PowerLimit_Update(.25, 40, 2, 270);

Returns 260

Test case 3 (POWER_THRESHOLD_kWh condition checking):

PowerLimit_Update(.25, 40, 3, 200);

Returns 150

Test case 4 (SOC derating checking):

PowerLimit_Update(.1, 40, 2, 200);

Returns 66.67

Test case 5 (SOC end derating checking):

PowerLimit_Update(.05, 40, 2, 200);

Returns 0

Authors: Adam Wu, Anna Lee

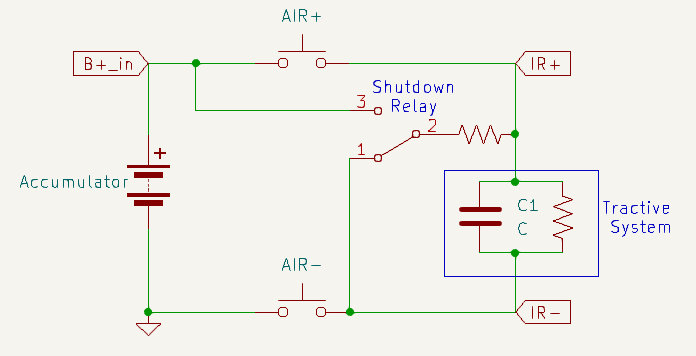

Pre-Charge Circuit

The pre-charge circuit is a subsystem that ensures that the accumulator (battery) will charge safely by limiting the inrush current to the car’s tractive system when the car is first powered on. The tractive system (TS) refers to the Inverter and Motor of the car as a unit. Limiting the current protects the rest of the system from potential damage. Accumulator-TS current doesn’t actually flow through the PCC , but rather the PCC will monitor their respective voltage levels and control the relays which connect Accumulator and TS. In the event of a shutdown, PCC is able to control relays and completely disconnect the accumulator from the TS. Watch this video for a great explanation on why we need such a system, ours is very similar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6-RndXZ5mR4

Hardware

How It Works

The PCC is split into two halves, high voltage (HV) and low voltage (LV). The HV side deals with accumulator and tractive system voltages which routinely go up to 400 V, while the LV side does not exceed 12 V. The FSAE rulebook specifies that there must be separation between these two voltage levels. However, we still need to communicate betweeen the two sides, as the teensy needs to read the voltages of accumulator and TS, both of which are on the HV side. In our circuit, this is accomplished using two optocouplers. Optocouplers achieve voltage separation utilizing an LED on one side (in this case HV) which will internally light up when there is a signal, and a phototransistor on the other side which will react to that LED.

HV Side

Here is a schematic demonstrating our system. The PCC is constantly reading accumulator voltage and tractive system voltage which come from B+_in and TS+, respectively. These are the most important connections to the system, and are fed into the board with a 2x2 molex connector. To read the voltages, the circuit utilizes two voltage to frequency converters, with input voltages that are stepped down with a voltage divider resistor network to be 1/10 of the actual value.

There are two Accumulator Isolation Relays (AIRs) in the PCC: AIR+ and AIR-. These AIRs are open air contact relays, capable of isolating very high voltages. In addition, there is a shutdown relay, which functions as a two way switch. We will refer to the shutdown relay as closed when it’s in position 1, and open when it’s in position 2. The precharge sequence and the states of these 3 relays during them is as follows:

Precharge: AIR+ is open, AIR- and shutdown relay are closed, TS is slowly and safely charged through the resistor. End of precharge: When TS+ is 70% of B+_in, the onboard teensy will tell AIR+ to close, bypassing the resistor. The system is ready. Error state: When we receive a shutdown signal through Shutdown_in or from a too fast/too slow precharge (see video for explanation if confused), AIR+/- and shutdown relay open. This configuration disconnects the accumulator and safely discharges the tractive system.

LV Side

Most of the complexity of the circuit are for the V2F converters, and those largely don’t need to be worried about. What is important to understand here is that the V2F converters convert an analog voltage to a signal with a frequency proportional to that voltage. Meaning: the V2F output signal is oscillating between 1 and 0. When vin is high, that oscillation will be faster, and when it is low that oscillation will slow down.

Using the optocouplers to maintain separation, that signal is fed to the teensy which then samples that data, and is able to control the rest of the circuit. The detailed implementation of these LM331 V2F converters involve capacitors and resistors which should be tuned to special values, but for this discussion of the PCC we will not dive into that.

Additionally, information on TS voltage, accumulator voltage, and error data are being sent over CANBUS to the CCM. This requires two teensy pins and utilizes a CAN transciever module.

Connecting Everything and Testing

Setting up the PCC can be confusing, and since it deals directly with accumulator voltage levels, it is important to understand how the wiring and connections work. Each of the connectors and what each pin is for are as follows:

HV IN TS+/-: positive and negative terminals of the tractive system B+_in: Accumulator-side AIR+ pin GNDS: Accumulator-side AIR- pin

POWER IN Shutdown_in: active high shutdown signal that triggers safe discharging of tractive system GLV-: Ground for GLV 12V: Positive terminal of GLV, or a 12 V power supply

IR+ Relay and IR- Relay Shutdown_in: active high shutdown signal that triggers safe discharging of tractive system GLV-, IR+_GND: ground signals

CAN Bus CANH/CANL: used for communication with CCM and other modules

Setup To test or use PCC, in addition to the board itself, you will need:

- two open air relays

- one 12 V source

- Accumulator or a 400 V power supply

- Motor+Inverter or some capacitor to represent the load

To hook up the accumulator to the inverter, take the two open air relays and decide which of them be AIR+ and AIR-. Connect one pin from AIR+ to Accumulator+ and one pin from AIR- to Accumulator-. The other pin of AIR+ goes to the positive terminal of the actual tractive system, and the other pin of the AIR- goes to the negative terminal of the tractive system. Definitely triple check this configuration. Make sure everything is isolated, it’s a good idea to use electrical tape over the contactors to avoid accidental shorting.

Now that the high-voltage components are hooked up, we need to connect the wires that allow PCC to monitor voltage levels. Connect the TS AIR+ pin to the TS+ pin of the HV IN connector, and the TS AIR- pin to TS-. Connect the accumulator AIR+ pin to B+_in, and the accumulator AIR- pin to GNDS. You will need to crimp wires and prepare a 2x2 molex connector.

Finally, we need to connect the PCC to the relays, so it can control them and open them in the case of a fault. The IR+/- ports correspond to AIR+/-, respectively. Simply connect them to their respective relays with Shutdown_in as the high input and with GND as low. After connecting CAN, the PCC is properly set up.

Software

Important Modules

General Overview

As mentioned in HV, the PCC is constantly reading the accumulator voltage and tractive system voltage and printing them to the serial monitor. As it does so, it transitions between four possible states: STANDBY, PRECHARGE, ONLINE, and ERROR.

- STANDBY (

void standby()): The initial/idle state of the PCC. Waits for a stable shutdown circuit (SDC). Opens accumulator isolation relays (AIR) and precharge relay. If the accumulator voltage is greater than or equal to the minimum voltage for the shutdown circuit (PCC_MIN_ACC_VOLTAGE), transitions into the PRECHARGE state. - PRECHARGE (

void precharge()): Closes AIR- and precharge relay. Monitors precharge progress, which is a function of the tractive system voltage and accumulator voltage. If the precharge progress is completed (prechargeProgress >= PCC_TARGET_PERCENT), checks if the target percentage was reached too quickly. If so, transitions into the ERROR state. Otherwise, transitions into the ONLINE state. If the precharge is too slow, it will also transition into the ERROR state. - ONLINE (

void running()): The status that indicates that precharge has safely and successfully completed. Closes AIR+ to connect accumulator (ACC) to tractive system (TS) and opens precharge relay. - ERROR (

void errorState()): The PCC error status. Opens AIRs and precharge relay.

epoch refers to system time (?)

main.cpp

void setup(): Initializes GPIO pins and the precharge system.

void threadMain(): Continuously reads accumulator voltage and tractive system voltage and switches between the four states based on corresponding conditions.

precharge.cpp

getFrequency(int pin): Gets frequency of a square wave signal from a GPIO pin.

getVoltage(int pin): Converts the frequency into voltage for accumulator or tractive system GPIO pins.

prechargeInit(): Initializes the mutex and precharge task.

prechargeTask(void *pvParameters): Handles the state machine and status updates.

void standby(), void precharge(), void running(), void errorState(): See General Overview.

float getTSVoltage(): Gets the tractive system voltage.

float getAccumulatorVoltage(): Gets the accumulator voltage.

PrechargeState getPrechargeState(): Returns the current precharge state (undefined, standby, precharge, online, or error).

getPrechargeError(): Returns current error information as an error code.

gpio.cpp

Initializes GPIO pins (shutdown control pin, accumulator pin, tractive system pin).

can.cpp

CAN communication.

Improvements + next steps

- Clean up code (get rid of duplicate and unncessary comments)

- Replace B+_in and TS+ wire housings which barely fit inside 2x2 molex connectors

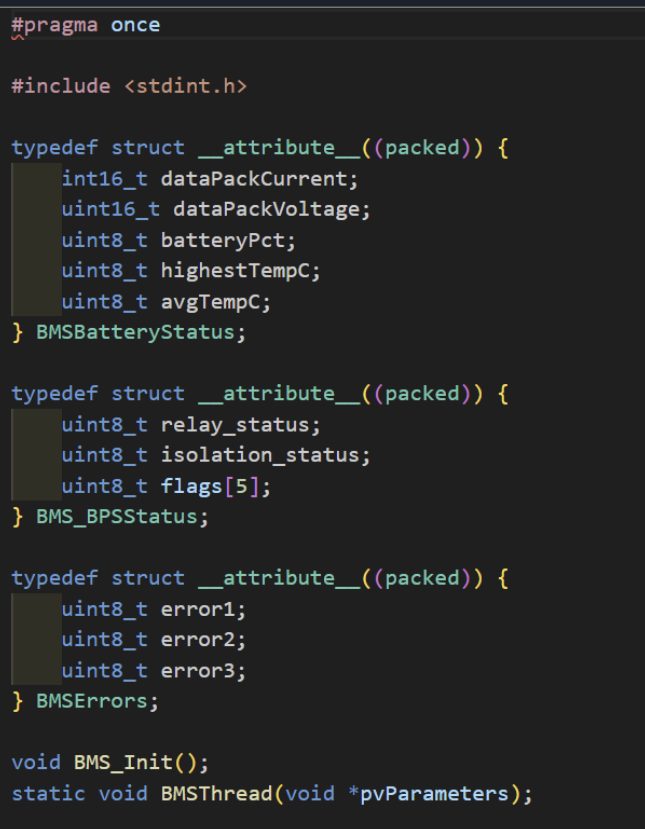

Author: Sebastian Ethan Basa

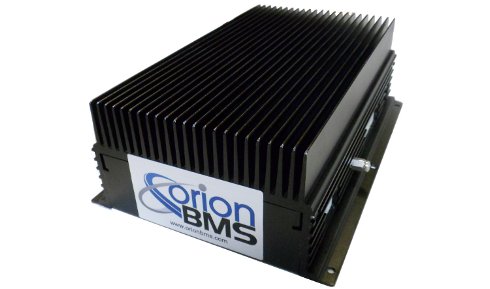

ORION BMS (Battery Management System)

The purpose of the BMS is to monitor various aspects of the battery, protect its lifespan, and report any faults with the battery.

The BMS transmits data via CAN messages which have their own unique CAN IDs. Using C++ and FreeRTOS, we can retrieve the CAN data from the BMS in the form of data structs, which can be interpreted and used throughout the code to control the car. Some of the data values that the BMS can transmit include battery cell voltages, temperatures, battery health, and fault conditions.